Before reading further, I’d like to warn you the content included in this essay is not for the faint of heart. It’s real-life stuff, but not happy stuff. Personally I am inspired by those who stand up in the midst of darkness, but some of what is included may be considered graphic.

Writing is a Human Right!

Writing is a craft, an art.

It is also a fundamental human right, a natural form of self-expression.

Article 19 in The Universal Declaration of Human Rights says:

“Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”

Think of this the next time you apply your words to the page. Think of this next time you make a post on your favorite social media platform.

It is yours, mine, everyone’s birthright to express.

Language is that powerful. So powerful, it must be protected—we use declarations and laws as our shields.

Yet, we live in an imperfect, complicated world, and our defenses are not impenetrable.

For example, we’ve re-entered a time when banning/burning books has taken center stage.

Banning books: this isn’t an easy issue to solve. And attempting to solve it is not something I aim to do here. But, the following quote may shine some light on the matter (into the darkness).

I still believe in man in spite of man. I believe in language even though it has been wounded, deformed, and perverted by the enemies of mankind. And I continue to cling to words because it is up to us to transform them into instruments of comprehension rather than contempt. It is up to us to choose whether we wish to use them to curse or to heal, to wound or to console.

- Elie Wiesel

What a great reminder—how am I using words, for what purpose? For what good?

The question is: does the act of banning a book infringe on the author’s basic human right “to freedom of opinion and expression” mentioned in the Declaration of Human Rights?

—I think it does.

Below is an incomplete list of books and authors banned in various states between 2022 and 2023 taken from PEN America’s Index of School Book Bans.

While there are many more on the list, I chose a selection of authors and titles that as an English major, I have read; most of them either in high school English class or during a college course.

James Baldwin, The File Next Time

Harper Lee, To Kill a Mockingbird & Go Set a Watchman

George Orwell, 1984

Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Slaughterhouse Five & Breakfast of Champions

Art Spiegelman, The Complete Maus: A Survivor’s Tale

J.R.R Tolkien, The Hobbit & The Lord of the Rings

Margaret Wise Brow, Christmas in the Barn

Geoffrey Chaucer, The Canterbury Tales

Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451

You would think the banning committee would second guess themselves, or at least look in the mirror and make a silly face, before placing 1984 and Fahrenheit 451 on the list.

These books directly confront the subject of banning or burning books, killing ideas, erasing history. I mean, duh!

While this is what is going on in America now, sadly, there are places in the world far worse.

For years, I have advocated for Chinese citizens and their freedoms.

While I don’t wish it to be so, perhaps censorship and human rights abuses are issues that will never be completely solved. They have been occurring since the dawn of time.

Maybe the best we can do is shine some light into the darkness. Shine light by raising awareness and standing up for others who’s voices are squelched.

This is exactly why I want to tell you about my real-life hero, Gao Zhisheng.

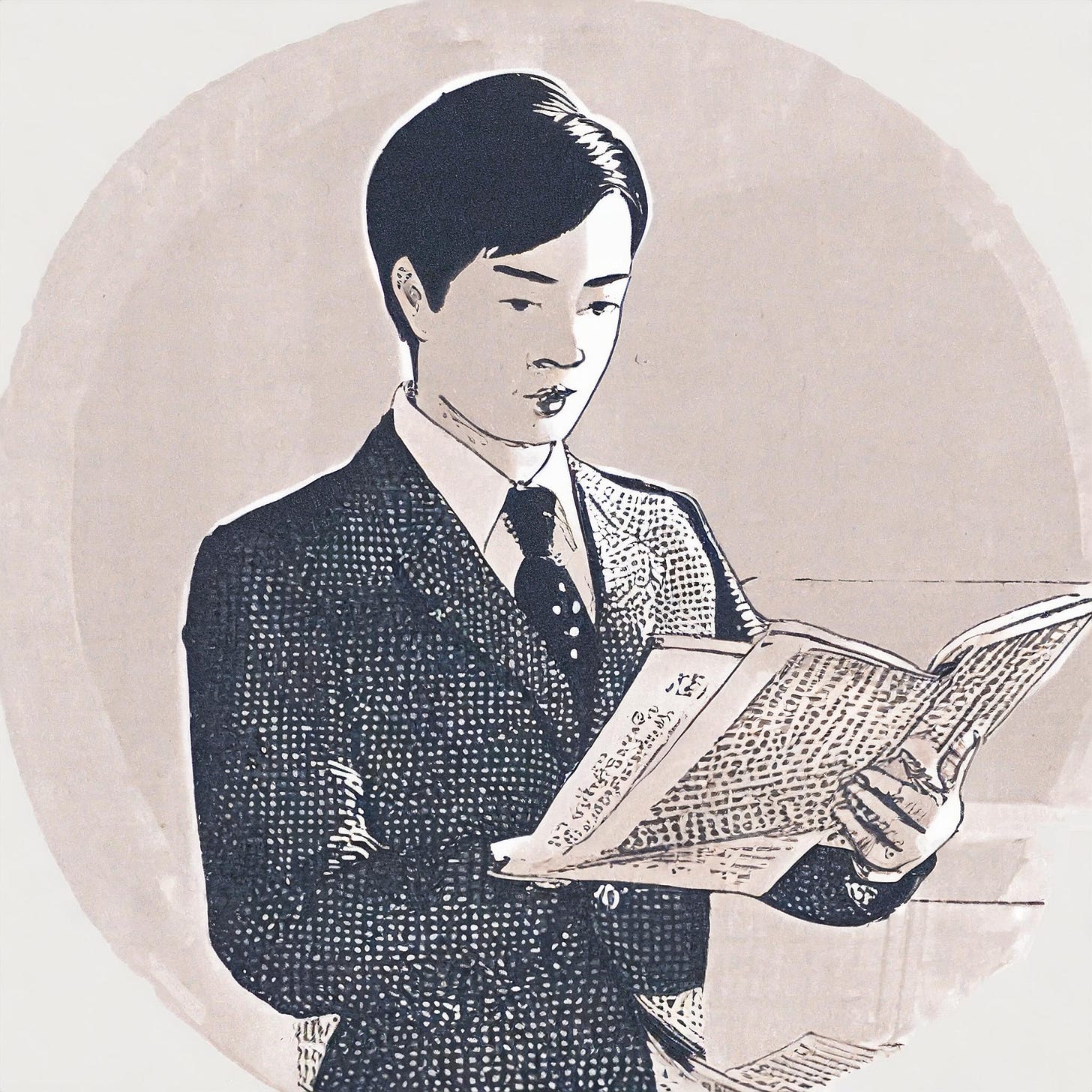

Meet Gao Zhisheng, who Amnesty International called “The Bravest Lawyer in China”

I have followed Gao Zhisheng since the early 2000’s when he started advocating for Falun Gong, a spiritual group severely persecuted by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

This was a time when there were only a handful of Chinese human rights attorneys who would speak out on behalf of such groups.

Doing so meant putting ones life on the line. This is what Gao did, and I’d like to share his incredible story.

Gao Zhisheng is not “one of” the bravest lawyers in China, he is indisputably “the” bravest one.

- Teng Biao, Chinese Lawyer & Political Activist

Gao was born in 1964 in rural Shaanxi province. His family, like others around them, lived in poverty.

One of seven children, Gao was raised in a cave. He learned to use the stars to tell time. His father passed away when he was only ten, which meant he needed to go out and find odd jobs to survive.

One day, while on the roadside selling vegetables, he came across an article in the Legal Daily News announcing that China would need 150,000 lawyers in the coming years. Gao taught himself law and passed the bar in 1995.

In 1999 Gao made headlines for winning the largest medical malpractice suit in Chinese history.

As a Christian, Gao began taking cases for those he deemed the most vulnerable—the poor, political dissidents, and those who sought religious freedom. Many cases were taken pro-bono.

In 2001 Gao was named "one of China's top ten lawyers" in an event co-organized by a China Central TV and the Ministry of Justice. This accolade was given to him by the same government that would soon persecute him to the brink of death.

In 2005, Gao wrote a series of open letters to the Chinese government advocating for the rights of house Christians and Falun Gong practitioners. This outraged the Communist government. They shut down Gao’s law firm and began their campaign, personally targeting he and his family, which would never cease.

Gao has been arrested and tortured multiple times. In August of 2017, he was taken into isolation through what is known as an enforced disappearance. His whereabouts remain unknown to this day.

His wife and children have since fled China for their safety and now live in the US. Human Rights Watch published a chronology of Gao’s life from 2001 to 2014.

To this day, if I could choose only one hero—it would be Gao Zhisheng.

His courage and spirit reach levels beyond the average person’s. What he has endured for others is unthinkable. Anyone interested, especially lawyers, should read his story: “A China More Just.”

I don’t believe I’ve ever seen someone take their role as an attorney to such a level of pure compassion and unflinching determination—and in the face of absolute evil.

Yes, evil is a strong word.

I’ve found many people become uncomfortable when it is used.

Rather than elaborate on what evil is in my own words, I want to share a few passages directly from Gao, written on November 28, 2007.

This is from his account of more than 50 days of torture in 2007 and is titled “Dark Night, Dark Hood and Kidnapping by Dark Mafia.”

*If you are sensitive to graphic descriptions, this is the section you want to skip.

… I was walking down the street one day and when I turned a corner, about six or seven strangers started walking towards me. I suddenly felt a strong blow to the back of my neck and fell face down on the ground. Someone yanked my hair and a black hood was pulled over my head immediately.

… The hood was pulled off of my head at this time. Immediately men began cursing and hitting me. “ **, your date of death has come today. Brothers, let’s give him a brutal lesson today. Beat him to death.”

…Then, four men with electric shock prods began beating my head and all over my body. Nothing but the noise of the beating and my anxious breathing could be heard. I was beaten so severely that my whole body began uncontrollably shaking. “Don’t pretend to do that!” I was shouted at by a guy whom I later learned was named Wang.

“…the electric shock prods were put on my face and upper body shocking me. Wang then said, “Come on guys, deliver the second course!” Then the electric shock baton was put all over me. And my full body, my heart, lungs and muscles began jumping under my skin uncontrollably. I was writhing on the ground in pain, trying to crawl away. Wang then shocked me in my genitals. My begging them to stop only returned laughing and more unbelievable torture. Wang then used the electric shock baton three more times on my genitals while shouting loudly. After a few hours of this I had no energy to even beg, let alone, try to escape. But my mind was still clear.

I’ll stop there. You may read the article in it’s entirety here.

Why, you may ask, did you share those terrible details with me?

In my experience working as an advocate for human rights, I have found the most important thing, when shining a light into the darkness (telling people necessary stories of human injustice), is to make sure you reach the human heart of the listener.

And also, to tell difficult truths. If you read Gao’s story—his words—and feel something, then the message has been delivered: a spark of humanity has risen inside you. This is a good thing. A very good thing.

It’s called waking up to a deeper sense of humanity. Re-becoming a human who cares for other humans. How can this not be good?

I say “re-becoming” because this is a process—a reminder; a nudge—to develop compassion, to grow your heart.

We all need this gentle nudge to grow.

It doesn’t just happen once. It’s a bit like exercising the heart. We do this many times in our lives. If you are moved by the suffering of another, you just strengthened your heart muscle.

Also, plain and simple—Gao deserves his story to be told. The suffering he has gone though for the sake of others is extraordinary. He is a real-life hero. A real-life superman.

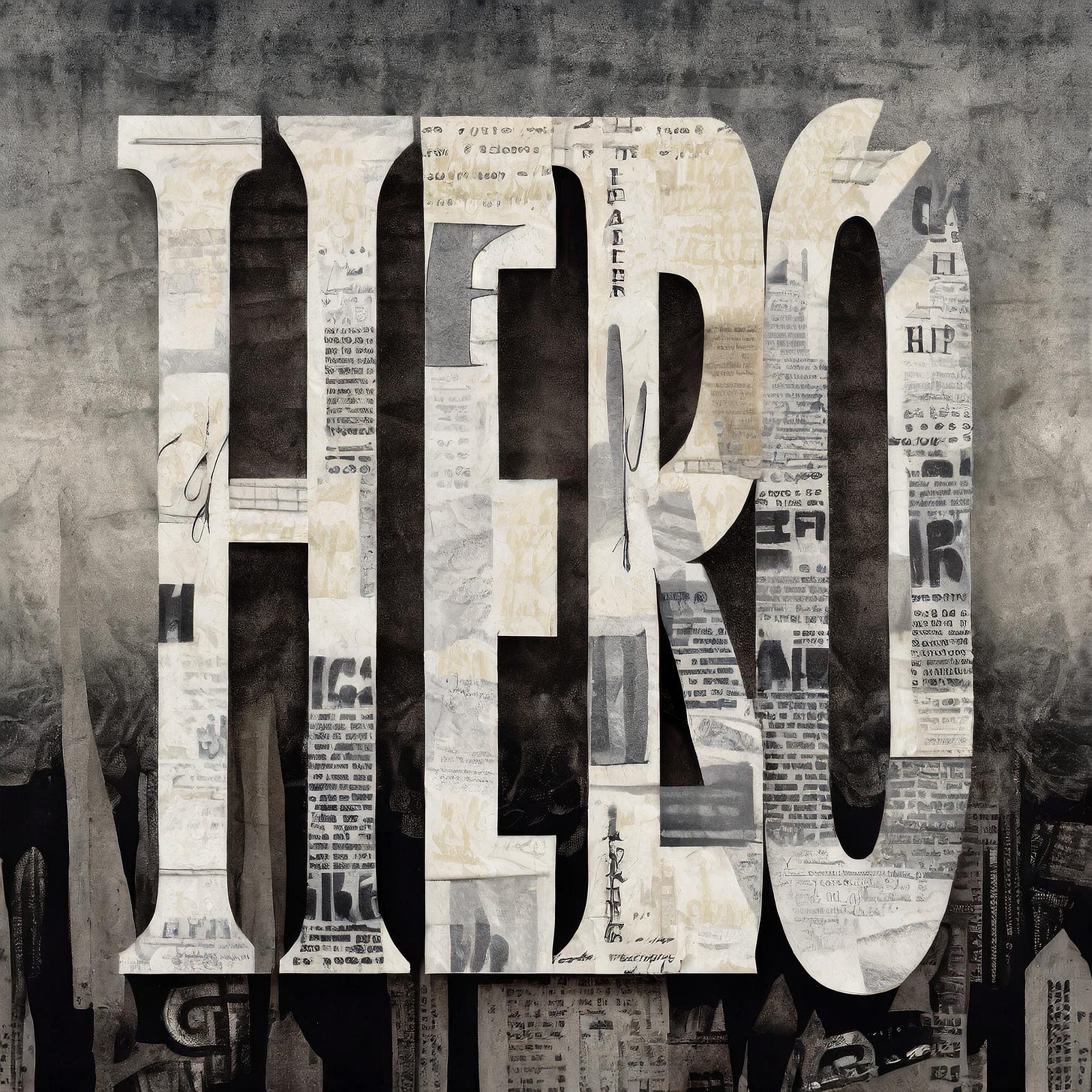

Hero—My Poem, After Gao Zhisheng

In the preface of A China More Just, Gao wrote:

“It is our misfortune to live in the China of this historical period. No one on this earth has ever had to experience or witness the suffering that has befallen us! Yet it is also our fortune to live in a China of this historical period. For we will experience and witness how the greatest people on earth banished this suffering once and for all!”

-Gao Zhisheng

I write poetry about all kinds of things. But my heart is happiest when I write a piece that touches on human rights—shining a light into the darkness.

And then to have it—this light, this poem—go out into the world to be seen. For this, I must thank OxMag for publishing “Hero” in its Issue 51.

OxMag, formally known as Oxford Magazine, is a literary & arts magazine edited and published by creative writing MFA students at Miami University. You can follow them on Instagram.

Here is the poem, with an unpacking of what is behind it below—

The main inspiration for “Hero” was both the preface quote from A China More Just along with some fascinating symbology I discovered years before about an antelope.

While reading about the origin of the word “antelope,” I found a number of sources stating it stemmed from “the word anthólops, first attested in Eustathius of Antioch (circa 336), according to whom it was a fabulous animal haunting the banks of the Euphrates, very savage, hard to catch and having long, saw-like horns capable of cutting down trees.”

Sorry, but fabulous animals are cool and must be incorporated into poems.

I decided this description reminded me of the sinister nature of the CCP, how it preys on the Chinese people. It’s savage and haunts the banks of good people’s lives.

I also was working with the long “e” sound in words throughout the poem, but particularly in the words at the end of the lines: trees, eve, CCP, Euphrates, appease, leaves—used 3 times, in both the following contexts: 1.) leaves, as in leaves from trees, and 2.) leaves, as in the act of leaving.

The placement and spacing of words was meant to create a sense of anxious movement that would happen to a person both physically and internally if they were being stalked, imprisoned and tortured by their government.

This anxiety would be all around, all encompassing—but there was a little bit of an empty space in the middle where one might be able to find some inner peace. Gao certainly held his center. The poem ends with a comma, because the story isn’t over. Gao is somewhere, we just don’t know where.

I pray he is released, and joins his family in the US to live the remainder of his days out in peace.

At that point, I’ll add a final line after the comma:

Until finally it Leaves.

Weekly Word—

How can we describe a man like Gao in one word?

Paragon—a model of excellence or perfection

Gao is a paragon of virtue. He is a paragon of goodness.

Merriam-Webster says:

Paragon Has Old Italian and Greek Roots

Paragon derives from the Old Italian word paragone, which literally means "touchstone." A touchstone is a black stone that was formerly used to judge the purity of gold or silver. The metal was rubbed on the stone and the color of the streak it left indicated its quality. In modern English, both touchstone and paragon have come to signify a standard against which something should be judged. Ultimately, paragon comes from the Greek parakonan, meaning "to sharpen," from the prefix para- ("alongside of") and akonē, meaning "whetstone."

This week I had fun with Adobe Firefly forming images for this essay. Here are a few from the extras batch:

Absolutely a power story!!! I want to share with my family, friends and clients. Very powerful Adam!